Dr. Robin Radcliffe is a wildlife veterinarian, specializing in rhinoceroses. His current research focus includes infectious disease investigations for Indonesia’s highly endangered rhinos as well as ground-breaking work airlifting rhinos that earned his team an Ig Nobel Prize. With his work through Cornell University, he travels the globe, often traversing rough terrain and uneven surfaces. That wouldn’t seem like a big deal, but Robin has knee instability. In fact, he’s dealt with it for the last 40 years. This instability has added a degree of difficulty to his work, which he’s taken in stride. He has to be careful about how and where he walks, watching for uneven surfaces and anything that might cause his knee to hyperextend.

Robin’s knee problem began with a low impact injury. He slipped on some ice when he was a teen. (Something that happens often if you live in Wisconsin.) At the time of this injury, his knee swelled and he saw his local family physician who withdrew the build up of fluid out of the knee. Robin says this was the beginning of his knee instability.

Rhino hanging in the air, being transported in Namibia.

He saw a surgeon who told him he had injured or torn his PCL (Posterior cruciate ligament), a large stabilizing ligament in the knee. He was also informed that PCL surgery frequently yielded unsatisfactory results. He decided to “deal with it” and forgo the surgery. Braces were made for his knee, to keep it stable, but he found them to be too painful to use. Instead, he participated in exercises that kept his quadriceps muscles strong. He took up biking and any other exercise that helped strengthen the leg muscles. However, his knee remained susceptible to hyperextending, especially when on uneven ground. Even when sitting to read a book, he found it necessary to place a support under his knee to prevent hyperextension as he relaxed. It just became a way of life for him to constantly keep his knee from hyperextending.

When he was in his 30’s he went to a University referral center that specialized in complex injuries to the knee. Again, he was told he had a torn PCL. This was determined by the doctors and residents at the center, due to the observation that Robin had a “Posterior drawer sign.” His knee showed a sag in the tibia relative to the femur, a classic sign of a torn PCL. The center offered no solution to his problem and instead asked Robin if he could undergo additional stress radiographs so their residents could learn to diagnose PCL tears reliably.

A few years later, he saw another surgeon who did an MRI and told him his PCL was not torn, just stretched. Once again, Robin decided against surgery and reconstruction.

During these years, Robin conducted his own research. Everything he read discussed the “Classical sign” of a torn PCL being the posterior drawer sign. He eventually came across Dr. Robert LaPrade’s website which explained PCL tears in greater detail. He was aware that the PCL is one of the strongest and thickest ligaments in the knee. Upon exploring Dr. LaPrade’s website, he discovered that PCL injuries account for only 20-30% of cases, often resulting from significant events such as car crashes or forceful impacts in contact sports. This injury profile did not fit Robin’s low impact accident on the ice. Additionally, he learned that neglecting PCL repair could lead to significant osteoarthritis in just 4-5 years. Robin had minimal arthritis in the knee, even after 40 years of knee instability. Exploring Dr. LaPrade’s website prompted him to delve even deeper into his research, sparking the first inklings of doubt about whether he truly had a torn PCL.

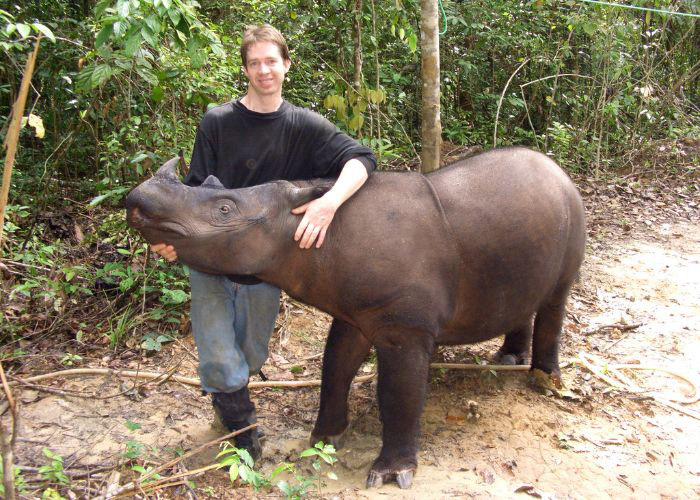

Robin with a Sumatran rhinoceros from Indonesia named Rosa.

Robin decided to visit Dr. LaPrade in Minnesota. Dr. LaPrade obtained a new MRI and inquired about the original injury when he was a teen, making note of the injury and what had occurred. After the review, MRI and patient history, Dr. LaPrade immediately knew what was wrong with Robin’s knee. The slip on the ice as a teen resulted in more than just a knee injury—it impacted the growth plate. This injury led to premature closure of the growth plate, resulting in an improper growth pattern for his tibia and adversely affecting the knee joint. As a consequence, Robin’s knee developed a noticeable crookedness with a name not unlike that of a Harry Potter spell: Genu Recurvatum. Surprisingly, there was nothing wrong with his PCL; rather, his knee instability was a consequence of the growth plate incident.

The anterior slope of a “normal knee” is 9 degrees. Robin’s knee measured at -2 degrees. Dr. LaPrade explained that he could fix Robin’s knee with a new procedure he helped pioneer called an Opening Wedge Osteotomy. The procedure is performed by very carefully, surgically cutting the bone to about 1 cm of the opposite side. This is done using various osteotomes and other specialized tools and is usually done from the inside part of the tibia. The bone is held open with a plate and wedge, together with a bone graft and screws. For Robin, the correction needed was significant, 11 degrees in all.

Having been told for 40 years that he needed a PCL reconstruction with a small chance of success, Robin was cautious. He sought reassurance from Dr. LaPrade about the success rate of the wedge osteotomy, who confidently affirmed that the procedure if done properly would offer a cure – not something that is all too common in complex knee problems having a duration of nearly 4 decades!

Three months later, after crutches and physical therapy, Robin’s knee is stronger than ever. It no longer spontaneously hyperextends. He feels strong and quite grateful that he never underwent surgery for PCL reconstruction (which would not have given him the desired outcome.) The persistent ache in his knee is gone, and he no longer has to prop his knee up to keep it from hyperextending.

Robin gets to hug Rosa

“Timing is everything” Robin told us. “This procedure hasn’t existed for 40 years until Dr. LaPrade and his colleges developed it.” Through his own research, he found Dr. LaPrade’s website and essentially his own “cure.” Here is what he had to say in a recent patient review:

“I was never more surprised when Dr. LaPrade walked into the exam room at TCO and informed me that my Posterior Cruciate Ligament (PCL) was normal! The surprise came from 4 decades of consultation with some of the world’s best knee surgeons (including University referral centers) who all agreed that while my case was unusual my diagnosis was the same: a torn PCL. Along the way some of the doctors offered PCL reconstruction surgery as a possible solution, but with poor prognosis I avoided all surgery for nearly 40 years. The diagnosis from Dr. LaPrade’s Team was not a PCL tear, but rather an old injury to my tibial growth plate that caused the posterior sag that is a classic sign of PCL damage. The solution? Dr. LaPrade performed a wedge osteotomy, a procedure he helped pioneer, and my knee is nearly back to normal just 3 months after surgery, without the sag and instability I had lived with for so long.” Robin R.

Robin with his daughter and a black rhino in Namibia

– Special thanks to Dr. Robin Radcliffe for sharing his story.