Description of a Dislocated Knee

A dislocated knee is an uncommon knee injury seen by orthopaedic physicians.

A knee dislocation typically happens after a traumatic fall, high-speed car injury or a severe sporting accident. Sometimes, a dislocated knee will go back (reduce) into place on its own or with assistance, but this is a very painful and complex process patients will often need to be put under anesthesia or be given a pain block to reduce the dislocated knee.

Dislocated knee symptoms include:

- Physical deformity – crooked appearance

- Severe pain

- Numbness below the knee

- Absent or diminished pulses in some cases

A dislocated knee is a very serious injury. It is very important that the vascular and nerve function status be determined at the time of injury. For more severe knee dislocations, a CT angiogram may be needed to determine if a potential popliteal artery injury exists. In addition, up to 35% of all dislocated knees also have nerve damage; this should be carefully evaluated at the time of injury, mainly for the common peroneal and tibial nerves.

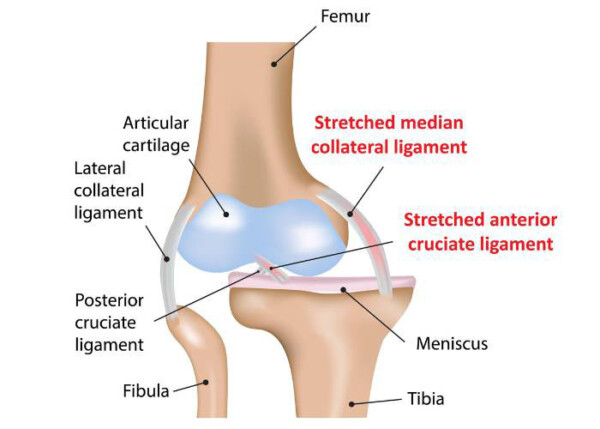

Most dislocated knees involve injuries to three or four of the major knee ligaments. These include the ACL,PCL, posterolateral corner, and the medial knee structures (including the medial collateral ligament and posterior oblique ligament). In addition, there may be injuries to the medial or lateral meniscus, the articular cartilage, a fracture or patellar tendon injury. It is very important to carefully assess the injury both on history and physical exam – it is also important to obtain x-rays, an MRI scan, and other studies as necessary.

Have you sustained a knee dislocation?

There are two ways to initiate a consultation with Dr. LaPrade:

You can provide current X-rays and/or MRIs for a clinical case review with Dr. LaPrade.

You can schedule an office consultation with Dr. LaPrade.

(Please keep reading below for more information on this condition.)

Dislocated Knee Treatment

It is well recognized that the outcomes of knee dislocation surgery are best in the hands of surgeons who perform them regularly and in large numbers. This is important due to the requirement of having a familiarity with injury patterns; a well versed surgical team, and a varied supply of allograft ligaments for reconstruction and other factors. Dr. LaPrade is able to offer all of these components to each patient that comes to him with a dislocated knee or any complex knee injury.

In general, the results of a dislocated knee are best if they are treated within the first 3-4 weeks of injury.

Confounding factors that can affect a dislocated knee include:

- Popliteal artery bypass surgery

- Blood clot

- Significant amount of swelling

- Knee stiffness

- Abrasions or lacerations which may require a delay in surgery

Any associated lacerations or abrasions of the knee may also need to be carefully evaluated for the suitability of surgery to help minimize the risk of infection.

While there is some discussion as to whether the surgical treatment of a dislocated knee should be staged – the collateral ligaments are repaired/reconstructed first and then 6-8 weeks later the cruciate ligament reconstructions are performed – we strongly believe all of these injuries should be treated at once and in one surgery if possible.

Dr. LaPrade and his team are very experienced in knee dislocation surgery; the goal during surgery is to complete the surgery in an efficient and effective manner. Our usual recommended treatment for a dislocated knee is to reconstruct the ACL with a patellar tendon allograft, double bundle PCL reconstruction with an Achilles tendon and tibialis anterior allografts, repair with an augmentation of the medial knee structures or to perform a direct reconstruction of the medial knee structures, and to perform a concurrent hybrid repair and reconstruction of the posterolateral corner structures as needed. Our preference is to repair meniscal tears rather than to resect them when possible.

Post-Op

Research shows that 20-25% of patients need a second surgery to address stiffness, this can happen when the patient does not begin physical therapy exercises immediately after surgery. Dr. LaPrade strives to achieve a minimum of 0-90° range of motion on the first day of physical therapy after surgery to lower the risk of future surgery. This has proven to be successful in minimizing postoperative stiffens in our treated patients.

A dislocated knee is a very complex injury and, in general, there is no “cookbook” recipe to address them. Each patient has a unique injury pattern that must be assessed when making a surgical plan. However, a careful assessment, utilization of the physician’s knowledge and having the patient work with a well qualified physical therapist and rehabilitation protocol typically gets patients back to normal activities and, more often than not, to a high level of sporting activities.

Knee Dislocation FAQ

1. What causes knee dislocations?

It is important to determine the actual pathology with a knee dislocation. A kneecap dislocation is different than a dislocation of the main joint of the tibia, the tibiofemoral joint. The treatment of a kneecap dislocation is different than that for a complete tibiofemoral dislocation.

A complete tibiofemoral dislocation is a surgical emergency. It is important that the arterial supply of the knee and the underlying nerve status are clearly checked. A workup to ensure that an arterial injury is not present is essential, which would include the checking of pulses, obtaining an ankle brachial index, and a CT angiogram (if indicated).

2. What does a knee dislocation feel like?

Most patients with a knee dislocation have severe pain. They are usually unable to bear weight and their knee feels grossly unstable. If the knee stays dislocated, usually patients have severe pain and are unable to put any weight on their joint. If the knee dislocation self reduces, which can occur in athletic competition, then the knee will feel very unstable and most patients would only be able to take a few steps before they would collapse

3. What prevents knee dislocations?

Most knee dislocations are caused by a significant trauma, so prevention is very difficult. For sports-related knee dislocations, making sure that one is appropriately rehabilitated after an injury, or has excellent baseline strength, can minimize one’s risk of a knee dislocation. In traumatic dislocations, such as a fall from a height or a motor vehicle accident, it would be difficult to prevent a knee dislocation.

4. How to prevent a knee dislocation again?

Prevention of a tibiofemoral dislocation would depend upon an appropriate workup for the artery and blood supply and then having surgical treatment. After this, ensuring that one has a maximal return of strength and stability as well as possibly using a knee brace would minimize the risk of a recurrent tibiofemoral dislocation. These are quite rare.

The prevention of a kneecap dislocation depends upon an appropriate workup to determine the risk of redislocation, as well as obtaining appropriate post-dislocation rehabilitation. Patients who have a high-riding kneecap or have a relatively shallow trochlear groove, have a higher rate of kneecap dislocations, even with proper rehabilitation. However, the rate of redislocation is still less than 50%, so following a proper rehabilitation program would be indicated in these patients.

5. Can a knee dislocation occur when sitting cross-legged?

It would be very difficult to have a tibiofemoral knee dislocation occur when sitting cross-legged.

However, if one does have a high-riding kneecap and a very flat trochlear groove, then a lateral patellar dislocation could theoretically occur when sitting cross-legged. In most circumstances this would be very rare, but it could occur with patients who have had repeated dislocations of their knee cap previously.

6. Can a knee dislocation happen when kneeling?

It would be highly unlikely that a tibiofemoral or a patellar dislocation would happen when kneeling.

7. What is the recovery time for a dislocated knee?

It is commonly felt that a tibiofemoral knee dislocation should be operated on rather than treated with a brace or casting. This type of treatment was performed about 20 years ago, and has since been demonstrated in systematic reviews to not have good outcomes. Therefore, it is generally felt that a dislocated knee should have a single-stage multiligament reconstruction. The recovery time for this can be quite long, varying from 9-15 months in some circumstances. This can be dependent upon the patient’s age, their overall weight, and if there are other injuries, such as meniscal tears, cartilage injuries, or fractures, which can significantly affect one’s recovery from a knee dislocation surgery.

8. Does a knee dislocation require surgery?

Most knee dislocations do require surgery. Those that are low velocity or sports-related injuries usually will have recurrent problems with the knee feeling unstable due to the torn ligaments if they are not concurrently reconstructed. Those that have very high velocity knee dislocations with fractures may have such damage to their knee and the cartilage surface ,as well as scarring, that a multiple ligament reconstruction may not be possible after the fractures are fixed. It is also possible for those who have nerve or vascular injuries that a ligament reconstruction may not be indicated if the knee gets severely stiff after a vascular repair or if the nerves are not looking well.

9. What causes a knee dislocation?

A knee dislocation is usually due to significant trauma. It can occur in sports, motor vehicle accidents, or those patients that are severely overweight when their weight shifts and they cannot catch themselves. These latter injuries are called ultra-low velocity knee dislocations and can be a very severe injury.

10. What are the symptoms of a knee dislocation?

If the knee dislocation is still dislocated, the knee will have an obvious severe deformity. If the knee dislocation slips back in, as soon as the athlete or patient tries to bear weight, the knee will often feel grossly unstable in multiple directions. Any numbness or tingling of the leg and foot in these circumstances is concerning because it may indicate a very serious injury.

11. How should one relocate a knee dislocation?

A true knee dislocation of the tibia and femur should be reduced by a medical professional. This is because there is a chance that there could be a fracture or other injury also mimicking a knee dislocation, so an assessment of this must be made prior to attempting a reduction of a dislocated knee.

12. What should one do with a vascular injury with a knee dislocation?

A vascular injury that requires surgery with a knee dislocation is a true emergency. The rate of amputation for those artery injuries that are not repaired within 8 hours is 90%. Therefore, one needs to be treated as soon as possible at a trauma center that can deal with a vascular injury after one has this particular injury with a knee dislocation.

13. How does a knee dislocation occur in football?

Knee dislocations are rare, but still can be present due to an injury in football. They usually occur when an offensive player is planting their leg and a defensive player hits them from the side. Some of these injuries have happened on national television coverage and can be quite gruesome, but this common mechanism happens across North America in multiple locations in football.

14. What is the difference between a knee dislocation and an ACL tear?

Knee dislocations occur when the joint slips on itself and becomes stuck or it could slip back in after a dislocation, but there are multiple ligaments that are torn. There are some occasions when a knee can be so unstable with an ACL tear that it can actually slip and “perch” with the tibia stuck on the anterior aspect of the lateral femoral condyle. This would be considered to be a KD-1 knee dislocation with only one cruciate torn and the collateral ligaments may still be intact. They are rare, but they do occasionally present. In these circumstances, the athlete is usually lucky that they did not tear anything else with this mechanism.

15. What is the incidence of a popliteal artery injury with a knee dislocation?

The incidence of a popliteal artery injury varies depending upon the mechanism of injury and whether there was a low energy or a high energy dislocation. Low velocity, or low energy injuries, which most commonly happen in sports, have a low percentage of popliteal artery injuries, which is probably 1% or less. However, those in high velocity injuries, such as a fall from a height or a motor vehicle accident, may have an incidence of a popliteal artery injury of 40% or more.

16. What nerves are usually injured with a knee dislocation?

The most common nerve that is injured with a knee dislocation is the common peroneal nerve. This will often present as a foot drop. Tibial nerve injuries are less common and usually are due to very severe high velocity knee dislocation injuries.

17. What is the prognosis after surgery for a knee dislocation?

The postoperative prognosis after a multiligament knee injury surgery depends upon the amount of energy that is involved with the original injury. Lower velocity knee dislocations have a good chance of being able to return back to most activities of daily living and some athletes can return back to sports. However, high energy knee dislocations commonly have multiple other injuries around the knee, including nerve, vessel, cartilage, or meniscal tears and tend to have more stiffness associated with their ligament reconstructions, so their overall function is not to be as good as those with a lower velocity knee dislocation surgery.

18. Can a knee dislocation lead to an amputation?

Yes, knee dislocations can ultimately lead to an amputation. Unrecognized popliteal artery injuries have a 90% amputation rate after 8 hours. In addition, if there are some open fractures below the knee dislocation that do not heal or if there is a nerve injury that does not allow good function, the patient could end up with an amputation. Thus, it is important to be treated as soon as possible after a knee dislocation, especially if there is a change in one’s pulses or sensation on the affected lower extremity.

19. What is the usual surgical procedure for a knee dislocation?

The treatment of knee dislocations has evolved over the last few decades. Several decades ago, most patients were casted and allowed to scar in and we found that those patients did not do nearly as well as those who had surgery. While tools were still being developed and surgical techniques were still being refined, it was not uncommon to have a staged surgery where a part of the surgery would be done in one surgery setting and then 6-12 weeks later a second surgery would complete the overall treatment. As surgical techniques have evolved and surgical equipment has gotten better, the current recommendation is to proceed with a one-stage multiligament reconstruction where everything is treated at the same stage. This seems to allow patients to recover better, avoid having 2 big surgeries, and reduces the risk of stiffness because treating everything in one stage allows for early range of motion of the knee.

20. What are the emergency management steps for a knee dislocation?

Assuming that the knee dislocation is the only injury that the patient has, following the steps of checking the vascular supply, checking the nerves, and then assessing if there are any open wounds around the knee should first be performed. Once that is performed, if the knee is reduced, one can assess what type of ligaments may be associated with the tear because an on-the-field assessment is always better than one performed further down the line when the patient is guarding. If the knee is still dislocated, a medical professional may try a reduction maneuver, especially if there is a decrease in pulses, to try to reduce the joint back in place. The important thing is to first look at saving the limb, so checking the blood supply for the pedal and posterior tibial pulses and then checking the nerve function would be the first recommended treatment.

21. What causes a foot drop with a knee dislocation?

A foot drop is caused by an injury to the common peroneal nerve. The common peroneal nerve crosses the lateral aspect of the fibula about 2 cm distal to the fibular head. At this location, it is very vulnerable to a posterolateral corner injury and stretching, so any injury that involves the posterolateral corner needs to concurrently assess the function of the common peroneal nerve to make sure that there is not a foot drop associated with it.